2015 Conference Summaries

Writing within the Production Chain

Contents

The aim of this discussion is to approach writing as a step in the production chain rather than a solitary process. Considering various issues specific to TV series, what problems are there likely to be in writing, in the exchanges with storyboarders and throughout the production chain in general?

Moderator:

-

Alice DELALANDE

Manager of Funding Assistance for Audiovisual Fiction and Animation Innovation

CNCFrance

Xilam Animation

XILAM Animation was founded in 1999 by Marc du Pontavice, who is also the current president of the Animated Film Producers Union. The company has a vast catalogue of more than 1,500 episodes of popular series such as Oggy and the Cockroaches, Space Goofs, Rahan and more recently Paprika. Xilam's latest cartoon dialogue series, Welcome to the Ronks (52x13'), is directed by Olivier Jean-Marie.

Now in full production, Marie-Laurence Turpin explains that the idea for the series was to create a joint effort by associating the writing and storyboard team and using the dialogues written at the same time as the boards. The special feature of this project was to create a board-driven work with two partners: France Télévisions and Disney UK. The entire process and pipeline had to be set up in both French and English.

Jean Brune then presents additional changes to the storyboard explaining the steps of producing an episode: the exchanges with the broadcasters on each version, the translation into English for discussions with the story editor and into French for approval by France Télévisions. A story editor also works with them from Los Angeles serving as a bridge between the writers and a link with Disney as well as correcting dialogues.

The editorial team is composed of Jean Brune, a member of his English team, the story editor and a post-production person in charge of recording dialogues. Discussions and French and English translations are done at each step before final approval by France Télévisions. The first episode of the series is due out at the moment.

Question: Do you feel that the approval process weighed heavily on this project?

• J.B.: We had already produced Space Goofs in this format but for this project we only had one broadcaster. For Welcome to the Ronks, we particularly concentrated on the adventure aspect to keep in line with Disney. In addition, it was necessary to add translation at every step of production.

• M.-L.T.: There was a lot less dialogue for Oggy and the Cockroaches, while here we are using a writing style with a real emotional structure, which complicates matters. Much of the dialogue was also written by the storyboarders.<

Questions: What are the lessons you’ve learned? How have you worked differently from what you’re used to?

• J.B.: At first the teams were disconnected between the writing director, the technical storyboard team and the director. We soon realized that we were losing out on the story in the transitions between production phases. The text was too long and what sometimes seemed important in terms of emotional development of the character would get lost in favour of texts which we believed were secondary.

Mélanie Duval

Mélanie Duval oversaw the writing of Chronokids with Futurikon and was the writer and graphic designer on projects such as Mademoiselle Zazie, The Rabbids, Raymond, Rosie and other series. Starting out as an animator, she would complain about storyboarders and when she became a storyboarder she began complaining about writers who were writing texts that were too long with elements in them that were too difficult to stage. It was therefore important to find the right form of writing for the production.

Once she became a writer, she tried to write as clearly as possible so that the boarders could easily imagine her scenario but also relate to it individually. This means that the writer and boarder must be on the same wavelength so that each episode ends up resembling the writer's first idea.

Giving the example of Captain Biceps, for which she was both storyboarder and writer, the main character has a lot of muscles but is not very smart. Sometimes a fight scene would come up that should be suggested rather than shown as the series was for kids. The writers for this show were not part of the same company and Duval wasn't able to talk to them. The division of these two companies ran the risk of creating a 'Frankenstein script' that was constantly being changed and was not coherent with the original idea. She suggests that there should be regular meetings between writers and storyboarders as once a script is approved by the production company and the broadcasters, it becomes definitive and would mean too much extra work to change it.

How can you solve this problem of dialogue?

Josselin Charier

Josselin Charier specializes in 3D television series for the domestic and international market. He is a producer at Hari studio, founded in 2006 and acclaimed for such series as The Owl, Leon, The Gees or the more recent Grizzy and the Lemmings.

In answering the question about who is the link between writing and the storyboard, he talks about a collaborative experience and explains that the world of cartoon can be highly cloistered between the different functions because it is an industrialized process. Studio Hari essentially specializes in visual gags with no dialogue, inspired from the Golden Age of cartoons (Chuck Jones' Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote) that can not be written down as the gags need to be visualized.

Even writing in a direct style is not enough, so they have added a step between writing and the board where the director takes the script, makes notes, adding and deleting for the visual sequences, and may even create a 'rough' board. This way, the director personalizes the intentions of the script and transmits them to the storyboarder.

When they started The Owl they didn't anticipate the need to rewrite the visual sequences and worked with a team of storyboarders and animators. 100% of the rights remained with the writers and this has resulted in lump-sum earnings for the workforce. They are currently starting production on a new (78x7') series without dialogue, Grizzy and the Lemmings, with broadcaster France Télévisions and worldwide distribution with Cartoon Network.

To write the script they decided to hold a day of meetings with various creatives devoted exclusively to this task. Having many people writing can resolve narrative dead ends, ideas tend to come faster avoiding many revisions and each writer builds up an overall picture of the rules and regulations of the series.

Grizzy and the Lemmings features a conflicting duo based on a situation that generates a conflict then a meeting point midway that relaunches the scenario. The episode ends with a climax. By adding outside characters they soon realized that the original conflict was not working. Writing with a team of five showed them that the secondary characters should not be significant, and gradually everyone became aware of the restrictions related to the series, which helped to build common references.

Question: If the director is not the co-writer, what is his writing role?

• J.C.: We believe that the main job of the director is to be the cornerstone of the production and create this 'rough' board, which will be approved before starting the storyboard.

Laurent Sarfati

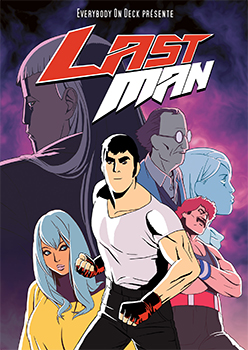

Laurent Sarfati is also an artist with many strings to his bow. He is a writer for live shows, TV series, feature films (It Had to be You), short TV series (La minute blonde for Canal +, Scènes de ménages) and music videos. He talks about Lastman, a new animated series taken from the comic strip by Balak, Michael Sanlaville and Bastien Vives.

After trying numerous teen/adult animation projects that came to nothing, he worked in collaboration with director Jeremy Perrin, who supervised the writing on Lastman, which is backed by France 4.

Making this project with such a modest budget forced them to develop new techniques. They thought about all the possible ways to save money and realized that three things were very expensive. One of these was the sets, which they reused, giving them a maximum of 8 sets per 13-minute episode. This process gives the animation its own style by creating special places for the characters and avoids using sets that will only be seen on screen for a few seconds.

They couldn't afford long texts for the scripts either, although if they are too short it becomes very difficult for the storyboarders. The use of still shots enabled them to save time encouraging writing in a maximum of styles and co-writing to discover new writing styles with boarders and illustrators to inspire more visual ideas.

Question: Were there constraints that you had already come up against or did you agree on these elements beforehand?

• L.S.: We had already agreed on certain constraints like the number of characters and sets, and we used as many tricks of the trade as we could to keep costs down. We also worked on the project at the Je suis bien content studios.

For example, we used writing techniques to facilitate the graphics and economize and created shots that were suggested rather than shown.

This meant that money could be used elsewhere, like in a short firework display at the end of one of the episodes. Co-writing with a director is wishful thinking as the writer is often poorly paid and the two are rarely synchronized. While Laurent was writing, Jeremy was overseeing the entire scenario. Writing, board and production can work in synergy. This saves time and builds a common vision.

Question: What is the budget of Lastman?

• L.S.: I don't know exactly. I'd say it was between 2,000 or 2,200 euros per episode of 13 minutes, which is low. The average is between 2,500 and 2,800 euros for an episode with dialogue. We had to make cuts everywhere, but the team is still eager to work on a project like this as everyone wants to be part of a series for adults.

Chris Nee

Chris Nee is a writer, producer and showrunner at Disney. She wrote for 20 years for animation, on television series like Henry Hugglemonster, The Doc Files and Angela Anaconda. She talks about Doc McStuffin, which she created and for which she is the showrunner. Season 4 is being written and will soon reach its 100 episodes of 30 minutes each.

The role of the showrunner is unique. He or she controls the entire project and oversees each step: the writing as well as voice recording, the animatic, the production of the music and the final mix. The showrunners must have a global vision of the project. The director can perform this function, but in this case it must be integrated in the job profile from the start. There are no unions to represent showrunners in the US and the system is very specific. There are no royalties and the writer doesn't know about all the details that will be adapted into the basic story. Most people who write have not been trained for animation. They don't have a clear idea of the overall process so are unaware that it shouldn't be overloaded.

Chris Nee's colleagues include some writers who have worked on SpongeBob Square Pants where the storyboards are visible during production. Each board panel would be reviewed for two days, and she has incorporated some of these methods in this new process She reviews the script all week with the directors and over discussions they set up the necessary compromises to eliminate errors. Everyone wants to manage problems downstream but they must be adjusted from the script phase because time is money.

She thinks that the problem with international productions is that everyone doesn't work in the same place and they need someone who has a global vision of the project. Scriptwriters tend to protect the scenario but the showrunner should know how to make the best decision for the director. The production works well when there is mutual trust because it is matter of time and budget. She writes with four employees, working together on a common process. She believes that you should write for the final product but the showrunner's role is to ensure continuity by putting everyone at ease. The job consists in bringing skill-sets together.

Question: There are very few showrunners for animation in France today. Should the writer, director or creator take on this job and should it be shared or not?

• C.N.: Each project is different. We are currently working on all these series and the constraints are not getting any better. We edit every week and a lot of work has to be coordinated at the same time. Broadcasters are very involved but if you have a showrunner you will have someone who will fight for your series.

We always need someone to fight for the spirit of a series and defend its interests. Animation is expensive and we need that person to deal with outside forces or broadcasters who may propose changes. Someone must be prepared to defend the project, if not, it becomes impossible to defend an aesthetic coherence, and the production becomes disjointed. It is a leitmotiv, a guideline given by one person.

Question of Marie-Laurence Turpin: How are you paid?

• C. N.: Disney finances most of our salaries. When you write for animation in the United States, you don't receive royalties. We don't have a union. I have a salary and I am responsible for all the writing and supervision.

Question: Can you briefly explain the beginning of the writing process?

• C. N.: Firstly, we ask the broadcasters what they think. We record the voices and don't work with storyboard artists from the beginning. We then produce the music and contact the storyboarders after this step. The animation is then done and reviewed with our clients. My programme is constantly moving but so far we haven't exceeded the budget or the schedule.

Question: Methods are different depending on each country and co-productions mean you have to collaborate with very different people. How does this work?

• C. N.: You have to have a lot of mutual respect during the storyboarding and scripting phases. We try to work with each other's strengths but it's complicated. It must be a collaboration. The first season is always difficult but everyone adapts. Whoever has the skills must have a structure for the entire team to work in the same direction but it's not easy.

Question: Do you discuss everything? How do you know what works?

• C. N.: Sometimes things don't work but in that case you need to leave the company. It's also a question of personal relationships and you must learn how people react. The writers don't know each other, and I think it's difficult if there are no opportunities to meet up or have a drink together.

Question to Laurent Sarfati: Does the team from Lastman play a part in the process?

• L. S.: This is my second comic strip adaptation to the screen and I think it's vital that the original team joins in. I wouldn't have worked on this project if it had not been possible.

We co-wrote with Jeremy and the three co-authors of Lastman and they wrote four more while we were making the episodes. You can't exclude the original author from an adaptation.

Question to Laurent Sarfati: What is your writing process?

• L. S.: We meet up with all the scriptwriters and lock ourselves up in an apartment for weeks. We put 26 blank sheets on the walls and fill them with Post Its and ideas. There is a main story and a sub-plot per episode. As a writer-director I realized that this series would not have been the same if there wasn't a mixed team. Once we agree on the pitch, we write a very detailed synopsis to avoid creating a step outline. The simplest step is then to convert the synopsis into a dialogue script.

The Annecy 2015 Conference Summaries are produced with the support of:

![]()

Conferences organised by CITIA

under the editorial direction of René Broca and Christian Jacquemart

LinkedIn

LinkedIn